Thermal Basso Rilievo: A case study for a Clapton Estate

![]()

Radley Square Estate, Clapton, London

The necessary reductions in energy use of the UK's existing 24 million homes have the potential to result in the most extensive overhaul of our built relationship with the climate. Fortifying the thermal line has been identified as a solution but perpetuates a culture of disconnecting with the surrounding environment. By giving form and space to the invisible energetic losses within the home, we speculate on the potential for creating improved spaces that generate awareness, agency and empathy with the wider ecological systems.

Human relationships to climate are cultural as much as they are technical. Only 300 years ago, our ancestors spent the vast majority of daylight hours outdoors, only coming into buildings for safety and shelter. The radical transformation of our (built) environment, which came about as a result of the industrial revolution, resulted in villages giving way to cities and life and work migrating from fields to floor plates (Baker 2004). This spatial transformation founded on an abundance of fossil derived energy resulted in a climatic rupture between internal and external environments (Iturbe, 2019). It is only then in the recent past, in evolutionary terms, that the human species had a far more intimate and adaptable relationship with their wider environment, accustomed to a climatic diversity now tempered within our current condition.

Radley Square Estate, Clapton, London

The necessary reductions in energy use of the UK's existing 24 million homes have the potential to result in the most extensive overhaul of our built relationship with the climate. Fortifying the thermal line has been identified as a solution but perpetuates a culture of disconnecting with the surrounding environment. By giving form and space to the invisible energetic losses within the home, we speculate on the potential for creating improved spaces that generate awareness, agency and empathy with the wider ecological systems.

Human relationships to climate are cultural as much as they are technical. Only 300 years ago, our ancestors spent the vast majority of daylight hours outdoors, only coming into buildings for safety and shelter. The radical transformation of our (built) environment, which came about as a result of the industrial revolution, resulted in villages giving way to cities and life and work migrating from fields to floor plates (Baker 2004). This spatial transformation founded on an abundance of fossil derived energy resulted in a climatic rupture between internal and external environments (Iturbe, 2019). It is only then in the recent past, in evolutionary terms, that the human species had a far more intimate and adaptable relationship with their wider environment, accustomed to a climatic diversity now tempered within our current condition.

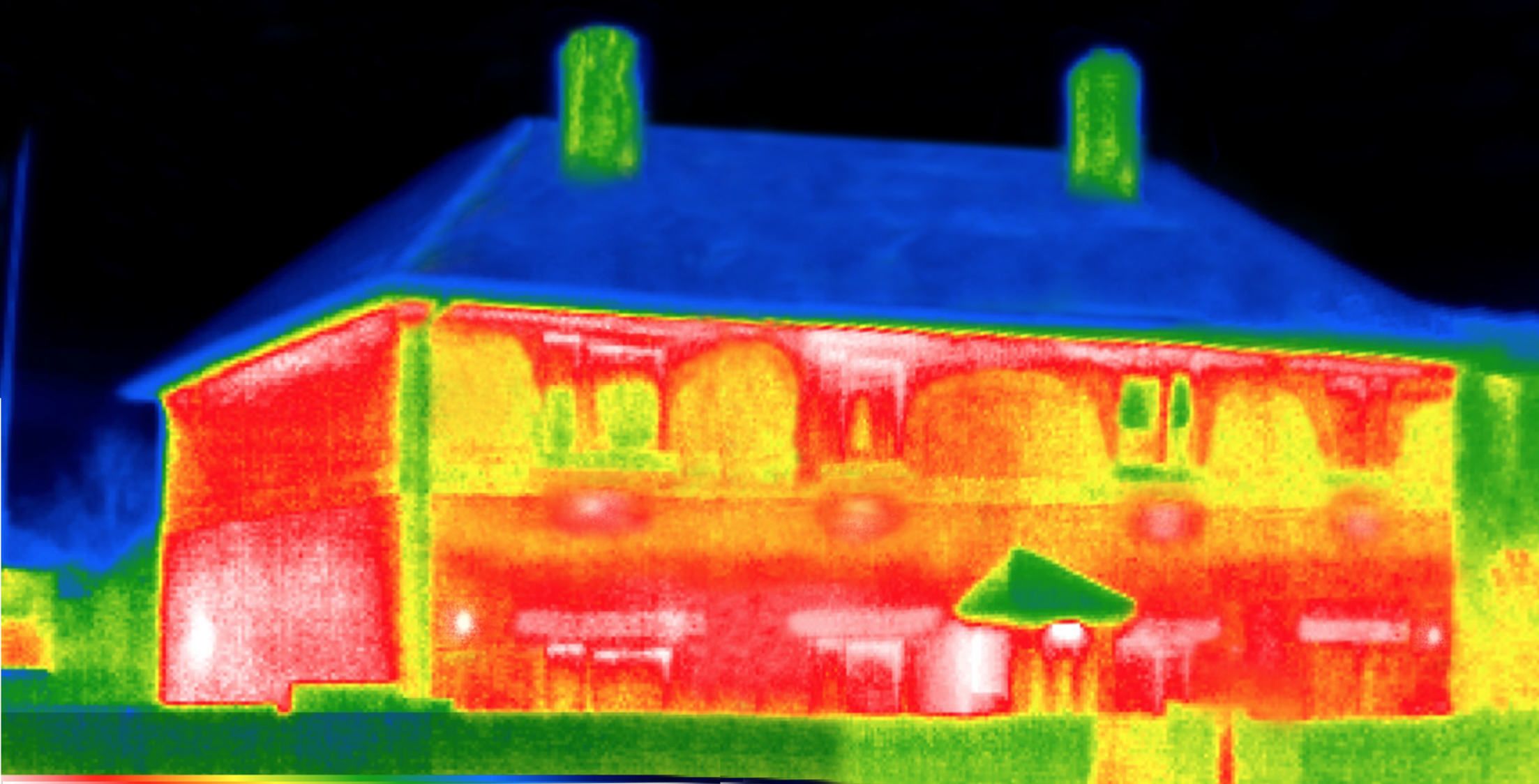

Thermal image of one of the estate blocks

The resultant culture, aspiring towards hermetically sealed interiors, has perpetuated in today's cultural imagination. In a strange twist this rift between interior and exterior has in fact been further accelerated by growing concerns of climate and ecological awareness. Thus, the consolidation of the building envelope as barrier to the environment establishes itself as the manifestation of both the issue and the solution. In practice, this often results in climatic considerations being marginalised to technical specification and mitigations, with ever more complex wall build-ups and mechanical systems detaching us further from the changing climate beyond.

Reducing load: Arguments within architectural discourse often disregard the urgency to tackle the need for more energy-efficient housing stock by placing the future abundance of renewable electricity and the upgrades to heating systems as suitable solutions that counterweigh the necessities of efficiency (Ruby, 2020). These postulations appear nostalgic of a past era of abundant energy however, with their actualisation restrained by pre-existing infrastructure. The necessary shifts to electrified heating systems will in fact result in far greater demand on the grid. This demand is limited by the load capacities across the grid, which limit the maximum consumption rate within dwellings, much like a narrow pipe restricting the flow rate along its length. To extend this analogy, it is not possible to increase flow through the pre-existing network of 'pipes' to satisfy the future new demand. Instead, we must assess and investigate ways of mending the leaks found along the pipes, thus reducing the source's overall demand.

Site plan

Site planIn order to reduce the energy demand of housing stock, we propose the reconfiguration of thermal envelopes through what we call an entropic approach. Entropy, seen as the dispersal of energy in a closed system that is not repurposed for any functional use, forms the framework from which to consider our found condition. Through this, we define an approach that carefully analyses the potential entropic losses in the various forms of energy, space, materials and cultural awareness dispersing within the system/project we approach. In doing so it is possible to recognise and repurpose these entropic conditions as the basis for invention.

Currently lagging in the energy transformation drive, the much-touted green homes grant sought to resolve thermal performance issues within existing buildings to the tune of a £2 billion stimulus, offering grants to homeowners for insulating walls and roofs. The scheme, however, has been cancelled, with only 10% of the government grants having been issued. Without dwelling on the scheme's failures, it is clear that managing this aspect of the transformation is technically, practically and socially challenging. Moreover, it begs whether there is a greater opportunity to be seen within this challenge and engage people with the issues we are facing? A fabric first approach is no doubt part of the solution, but could we go further? Is there a more ramified approach for the architect of our time to consider how we could reinhabit existing space? In doing so, we can then see these changes as an opportunity to adapt, add to and improve existing living situations whilst also reducing dwellings' energy use.

1:25 Model of the relief facade

Identifying: Until not long ago, we had a very different relation to how we mitigated heat within our homes. The combustible materials brought in to the home and ignited to produce heat created a clear correlation between resources and heat, heightening the perception of energy being consumed. Present home infrastructure breaks this one in one out relationship; Abstracting our link to energy to pure monetary form, thus removing the past cognition of large amounts of resources employed to produce heat.

Often, conversations with themes of efficiency, unknowingly exclude groups of people less acquainted with these subjects. Are there ways in which an intervention can not only achieve its architectural intent but also function as a vehicle for information, passively offering knowledge? In translating the project's task into a physical artefact, there is an opportunity to make energy flows evident and understandable (Bruther, 2018). Therefore, it is by giving form and space to the invisible that offers a challenge and engagement to the imagination of the user/audience. While some of the taken approaches will be hard to implement on a broader range, limited by access or site-specificity, their echo might have a much more significant impact. We find the project's outcome to be an opportunity to, even if marginally, try and proselytise any possible audience to care/understand, generating awareness, agency and empathy with wider ecological systems. Thus, each project will not only be functioning for itself as a closed cycle solution but hopefully engage on a much larger scale as well.

Control, Space, Qualities

Through the embodiment of these energetic flows, there also comes greater potential for the perception of control. Many studies have documented a direct correlation between the perception of adaptive freedom and thermal satisfaction (see Baker, . An exemplar case (Guedes 2020) which assessed office workers' comfort across Lisbon through the summer, found that a user's perception of control of window openings generated a greater sense of thermal comfort. Therefore, there is a psychological factor at play that should not be underestimated, with spaces that elicit the perception of control being key to comfort. This would suggest that we are more adaptable and accustomed to a more interconnected relationship between exterior and exterior than technical standards would imply. In pulling apart the thermal envelope, there is an opportunity to create a series of spaces of different qualities, each allowing for control whilst improving thermal efficiencies.

It is possible to transcend the accepted conception of the thermal line as protector from the environment to something more diverse, adaptable and flexible, allowing for different ways of living and fostering a more integral relationship with the climate. In generating opportunity for control and legibility, there is an often unutilised capacity within formal and spatial approach to the building envelope to generate awareness, agency and empathy within the immediate and wider environment.

These themes have been explored within the images which accompany this text. They describe a series of entropic interventions to an archetypal 1930's suburban housing typology. The addition of an external wall insulation layer is applied to the existing façade mapping the uncontrolled thermal losses through the elevation by contouring the added depth in accordance to existing thermal bridges. An additional unheated glazed zone is also added to the rear of the dwelling generating additional space and thermal threshold within the depth of the façade. Selected existing window openings are then enlarged and upgraded, opening onto the winter garden space to allow rooms to expand and contract in reaction to the wider environment. These adaptions serve as a first illustration of how necessary technical upgrades have the opportunity to create improved living environments. Interventions that through form and space look to re-establish a mutually beneficial relationship with the climate rather than continuing to isolate further from it.